By Vassilika Sarilaki *

The most powerful experience of art is when the work of an artist leaves one speechless. When one emerges from the mists of “ineffable speech”, as Valery defined it, no amount of verbal caresses can encompass it. Costas Tsoklis has reached such a celebratory moment, and he talks to us today, at the age of 76, about the most important work of his career. It is the “Oedipus in Conclusion”, a powerful, moving, human piece; masterful in the life messages it transmits; perfect painting and dramaturgy.

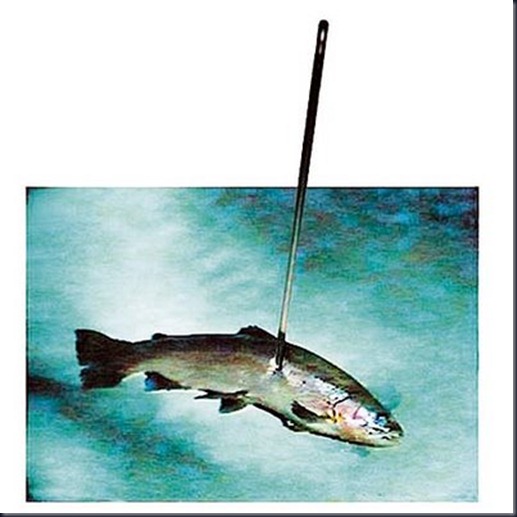

How did we get to this point? Tsoklis is an exceptionally prolific artist with 3,000 works and over a 100 solo exhibitions; a powerful present in representational art and a modernistic shock of installations and semi-three dimensional works testify to a particularly restless artist. The major digression, nevertheless, came about in 1986, when he presented to the Venice Biennale the video of the “Harpooned Fish”.

Since then, he has been absorbed in what is called ‘living painting’; the projection of a filmic image on a painted surface. Until then, with the uncanny talent and exactitude of an entomologist, he had been studying the intrinsic beauty of a stone, a rock or the sea indicating their metaphysical dimension, exercising a pagan worship in the gaze. Later, he combined painting to some extent with the three-dimensional, providing us with the charm of optical illusion.

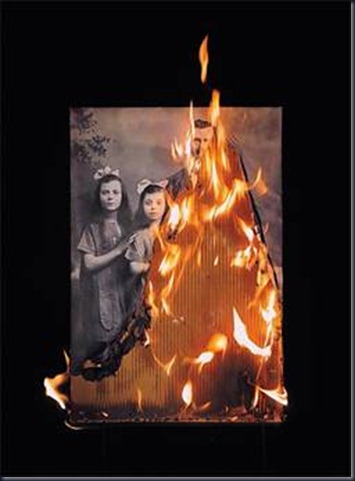

Since then, he has been absorbed in what is called ‘living painting’; the projection of a filmic image on a painted surface. Until then, with the uncanny talent and exactitude of an entomologist, he had been studying the intrinsic beauty of a stone, a rock or the sea indicating their metaphysical dimension, exercising a pagan worship in the gaze. Later, he combined painting to some extent with the three-dimensional, providing us with the charm of optical illusion. Then suddenly in 1986, he abandoned nature and turned to the mythologized human figure, in the sense of a Higher being with symbolic references to tragedy. In 1990 in France, he presented the installation Medea which was a faint video image projected onto huge painted areas, in the form of painting-performance. In 1997 came Artemis, in 2002, Angels of the Future, and in 2003 in Istanbul, the faded photographs of everyday, non-tragic “heroes”, who suddenly “came alive” with the use of a torch.

Today the myth of Oedipus is laid out in a continuous series of 13 dramatised episodes, which critically summarise his life, and together they transform the myth by grafting it with the burning wounds of this era.

Self-criticism and the final signature. I asked Costas Tsoklis if this work, with its autobiographical elements, is a stock-taking piece; his final signature. He replied:

First of all, I’d like you to take pity on me and don’t say final! Looking back, I have to say that the years, when I was doing my works in perspective and nature, were I’d say years of enthusiasm. Those works made a great impression on the public and this influenced me. But when you reach a certain age, you discover that nature and life have little to offer you because you have almost consumed your senses. As long as you wish to remain a person who speaks a universal language, and if you realise you have nothing important to say, you fall into an artistic void, (as happened in most of the 20th century when the artists got exhausted in the language rather than in what the language should have been saying) I thought that I should concentrate on what connects us with the universal philosophical culture. Since I was consuming the remaining reserves of my painting talent by mimicking nature, I felt a little like a tourist, that I was essentially doing touristy art. Therefore I tried to go deeper; to see what it was that would redeem the title Greek for me. So I turned to the myths, I lamented things lost. I hoped that with different compositions we could create new works. Photography and cinema gave us new ready-made images which, despite being crude, invited us to work with them. In the beginning, I admit I was satisfied with their impact and beauty. Later we were filled with a million such images and I felt that they were useless and superfluous unless the artist intervened to give them some meaning.

In this way I got to my recent work by using technology as a means and the myth of Oedipus as a pretext in order to express an art manifesto.

Promytheas, 2009

Patricide and conceit. I interrupted the confession of Costas Tsoklis by asking if perhaps he risked being charged with conceit for his identification with Oedipus, and what were – as he declares – the personal relationships with the myth. He told me:

I don’t think that I risk being misunderstood at my age. By simply getting into the theme, I discovered that, paradoxically, I too am an image, a shadow of this myth. Given that hardly any Greek artist could avoid the erotic relationship with our tradition, we had the desire to procreate with our mother. I am no exception. Then there are other coincidental elements in the myth. I too was thrown out on the street, I grew up in poverty and occupation, I survived. I also emigrated, I abandoned my country, I disputed on the way with passers-by, either spiritually or physically; and either out of jealousy or wilfulness, I could also have “killed” my father, my spiritual parents.

But wait, aren’t you exaggerating? You state in interviews that for years you tried to solve moronic riddles, how you sold your talent for money, that you made imitations of nature, and now, you are denouncing your entire modernistic period. Does this mean you regret the other Tsoklis you once were?

You can’t regret anything because you can’t take anything back. But I have the feeling that for many years I paid attention to the commands of the age.

To trends in other words?

To trends if you like. Perhaps when we are young, we want our work to reveal more of our ingenuity or our sensitivity and less of a goal. This is why I wrote somewhere that I wished I had been born wise and lost my wisdom gradually…

But it doesn’t happen like that… I want to say that I utterly appreciate your boldness in risking your successful, historical identity to propose a contemporary means of expression, which others of your generation have not dared, such as Kessanlis and Kaniaris. I believe it is this that further connects you to the work of young artists.

There was once a naughty boy who was loved, not to be ungrateful; a young man with a grand passion for love and life, but as an old man I don’t want to play the child. However, the fact that many characterise my work as new is due to a simple truth. There once was a pliable piece of dough susceptible to changing events.

What would Oedipus say today? The final question was how do the 13 episodes of the work relate symbolically to social reality?

It begins with a theme, as timeless as it is allegorical: drought. We all know how much Africa suffers and how many people die. There follows the image of Teiresias, the abuse of power and mutual extermination. Later, the abandonment and abuse of children. Instead of a child, I show a trapped lamb, a symbol of innocence. It continues with the desperate wanderer, a comment on the emigration we have experienced and which continues intensely today. Then, the senseless clashes and the symbolic patricide. Later an image of soft-pornography is presented; the blindness (a clear reference to painting), the blind man wanders through a nature he can’t see, which is what we do when we destroy nature by not being able to “see” it, and so we get to Kolonos. Sophocles described it as a divine, sacred place, laden with olive trees and vines where nightingales sang. I show an image of what a region has degenerated into today, which I convert into painting as all the images. Then there is the seizing of girls by soldiers, recording today’s violent scenes at peaceful demonstrations, and so we reach the end. The voice of God is now heard with thunder and lightening and the expurgation follows, my deepest desire is to be cleansed of my sins, which is untenable of course because I can’t take back my wrong-doings. And then he goes…Oedipus is lost in nature, and as in the play…we don’t know how it turned out. Promised nonsense, just as I sometimes promise, how “if you bury me here, your city will never be in danger” and some such bullshit. The others believed him! This is how he tried to appease them and somehow protect those who took care of him. Many people have taken care of me, even you in what you’re doing, and so I also wanted to create a similar atmosphere of security for you too through my work…

*Vassilika Sarilaki is an art historian

Hello there, just became aware of your blog

ΑπάντησηΔιαγραφήthru Google, and located that it is truly informative.

I am going to be careful for brussels. I'll appreciate when you proceed this in future. A lot of people shall be benefited out of your writing. Cheers!

Feel free to surf my site - herbalife blog