Jilly Ballistic: interview with New York City's best street and subway artist

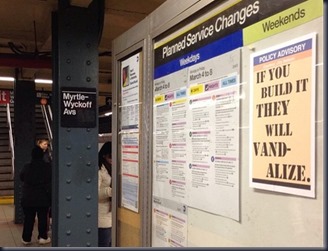

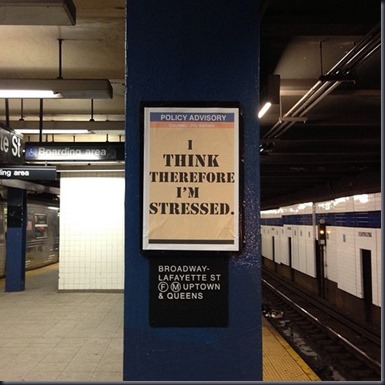

Jilly Ballistic: It wasn’t a decision, exactly, as much as a natural progression. It felt like the next step in where I was headed in this thing called street art. As any New Yorker, so much of your time is spent commuting and being in that subway space. After all this time it suddenly felt like: there it was, a blank canvas right before me. I can interact with it. Use it to speak. Art Noise: Do you feel that your message “breaks through to the other side”? Are you satisfied? Jilly Ballistic: The public is definitely listening. And I believe it’s because they want to hear something. I work in broad daylight, with New Yorkers around me on the platform or inside a train car. I can say from experience and interacting with the public that they are hungry. When I begin to put up work, they watch and then ask questions after I’m finished, mostly who’s portrait I’m putting up or why that particular Policy Advisory. After our conversation it feels as though they really appreciate the artistic endeavor. They’ll also take a photograph, which ends up being shared and commented on; suddenly a dialogue begins. That’s great stuff. Art Noise: I want to discuss with you some of your “Policy advisories”. F. e “If you build it they will Vand –alise”.. Some people say that you resort to Vandalism. In Greek Vandal is someone who destroys not he who creates works of art. This word comes from the French Vandalisme which refers to a barbarian German tribe who used to smash the noses and ears of statues because they were afraid that through these diodes the statues will acquire soul and become alive!

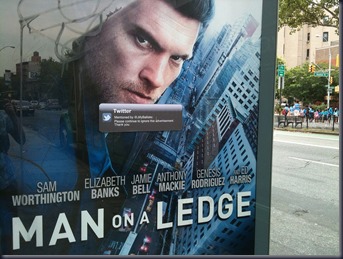

Jilly Ballistic: The politeness in some of the “digital” faux Mac or PC warnings, like adding Thank you or Apologies, adds to the humor of the situation. In a way I feel like I’m writing a short letter on the behalf of the public to corporations or the movie industry.

Jilly Ballistic: Being compared to Banksy was unexpected, to say the least. It’s flattering. Perhaps it means I’m on the right path in terms of getting messages out there, points made and communicating.

Jilly Ballistic: I do have several projects running at the same time, like you noted: the historical images, the “digital” work and the updated idioms as Advisories. More projects will come and go as well. It’s not that I prefer one of these over the other; it really all depends on the site. If I’m addressing an ad, I’ll put up an Alert or insert an image that is relevant to my commentary. But whatever it is that ends up being pasted to a wall, I hope to get a dialogue going, a few thoughts on the topic. Or even get a laugh.

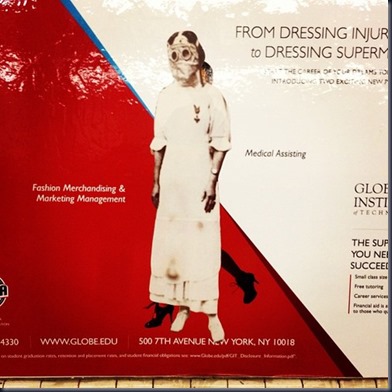

Jilly Ballistic: Yes, all the content is mine. So I have to thank Hollywood for their lack of ingenuity and companies for their lacking products. It’s actually their lack of faith in the public and what they are trying to pitch is what inspires me. Also, the subway system itseld is such a great space. Mixing the past and the present, they compliment each other and really show how little/far we have come in society. Art Noise: Public art is associated with social criticism and politics (in a large aspect). What’s your relation to politics? Banksy f. e did an installation during the Occupy Wallstreet. Would you do something like that? Jilly Ballistic: In a sense, I feel the military images I install within public spaces has a political undertone. It’s subtle and not clearly defined or in your face, per se. However, I’ll gladly head to the other end of the spectrum if the time is right and get a precise point across. My work is site specific, environment oriented and very-in-the-moment, so yes, I have no problem speaking out. Someone has to. Art Noise: Why do you resort only American imagery of WW1&2 and not use also imagery from other contemporary poor or war damaged countries to make the contrast with today’s situation? Jilly Ballistic: The 100th anniversary of the gas mask’s invention is coming up. I wanted to install the face of war theninto our world today. This face has changed, but not the behavior. It feels as though you can take the characteristics and decisions of our governments from a century ago and put them side to side with our governments today and see a startling resemblance. Art Noise: I saw your beautiful recent video https://vimeo.com/64965149 and I wonder: aren’t you afraid acting like this in front of the passengers? What if the police arrest you? What would the penalty be? How dangerous is it? Jilly Ballistic: Passengers are curious and conversational. Once you start talking about your projects and their purpose, people become welcoming to what you’re doing and understanding. When I explain the materials I use don’t damage property and cost nothing to remove, suddenly it’s the Law that seems radical not the artist. Art Noise: There’s no doubt that all this material you use costs. How do you manage your expenses? Is street art for sale? Jilly Ballistic: Every now and then I receive requests to install custom images in homes or offices. All of the Policy Advisories can be printed and shipped. So yes, if someone is interested in buying a piece or having one made, they just need to reach out. Art Noise: “Kill your television”. You have made a very beautiful “collage” by changing completely the meaning of a TV news ad simply by pasting the image of a soldier who shoots on TV. Do you really believe that TV can be killed for good by any media like Internet? Jilly Ballistic: Television needs to adapt to the internet age or it will certainly die, or worse: become irrelevant. More Reality TV shows won’t save the day. You need quality programming. Trust that the viewer can handle intelligent or controversial social material. Kill Your Television (36th St; Queens bound R/M), Photo: Jilly Ballistic Art Noise: You have lately posted a photo featuring an executive producer who proudly shows one of yours “Policy Advisory” affiches – framed!. We read: “Beauty is in the eye of the executive producer”. You have also criticized sexism by posting “sexism sells”. As a woman I like your gentle postfeminist approach…What do you think of sexist ads and the manipulation of beauty nowadays? You know, even an effort in Sweden to pass legislation against sexist adds has finally failed.

Art Noise: When I read your slogan “It’s all fun and games until morality makes it hurt” instead of reading the word morality I read mortality! Instantly my mind recalled the function of Synchronicity by Jung and I started making strange thoughts:

Jilly Ballistic: The plan is to keep going, to continue making work and experimenting; collaborate with other artists and locations. The plan is to go head first.

Thank you! |

Nomadic artists: Nostos* for the “bare – life”?

![Nikos Charalambidis, Rietveld's Red Blue Chair blocked in a traditional loom [2006] Nikos Charalambidis, Rietveld's Red Blue Chair blocked in a traditional loom [2006]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEhwq4ivq96zR2PTgNrgC2UoN3Pk7DRtSmupWRzfHOk_8gyMBhxwKTZ6SBIwG9WpXYTTp3YrTeJcXBC_T7EVVypW1SbqO_eTQBxXORlZ5-g9cZii0EaDepU5CRk2f7cEEmvmWnUiP5lHKGNd/?imgmax=800)

Nikos Charalambidis, Rietveld's Red Blue Chair blocked in a traditional loom, 2006

By Vassilika Sarilaki

What’s the role of cultural nomadism nowadays? How the artistic residencies influence contemporary artists? Do nomadic artists have a desire to experience the “otherness” and “bare-life” in any cost in order to find the truth for themselves and their artwork? What’s the result of comparing different cultures and having cross-cultural experiences? How valuable can be the concept of a nomadic art evaluation in everyday life? Do we still believe in postmodern values or something different is about to rise? We looked upon the nomadic experiences and artworks of four Greek artists who answered our questions and helped us to enlight the topic..

Displacement has always played an important role in 20th century art, starting from impressionism till nowadays. It is known that even some art movements were influenced by this. Artists known as fauves, -Gauguin, Matisse, e. t. c -were constantly travelling abroad to get some artistic experiences and inspirations. European people have always been migrating to USA for economical or other reasons and at the dawn of the 20th century (between 1850 and 1914) as Glynn, (2011) states “over 50 million Europeans migrated to North and South America. Ireland, Italy and Sweden contributed, over 15 million of these emigrants”. Artists’ emigration to America continued all along the Modernist period. In a way, we can claim that the New York’s abstraction movement was based on foreign artists. Moreover, the New Bauhaus was established in Chicago after the Nazi’s attack to Weimar. Fluxus was also a multinational movement expanded all over the world. Artists always travelled a lot and worked in different places.

Alexandros Georgiou, Group of Forgotten Gods, Mixed media processed photograph, National Museum of Contemporary Art

It is common knowledge among art historians that the avant garde in Modernism was built upon a number of artists, the great majority of whom, lived in the metropolises of Europe, the USA and Russia. Artists moved from poor countries to richer ones in order to have a carrier. Those days, however, travelling, staying abroad or moving to cities, such as New York or Paris, was a personal choice but not an indispensable move in order to become famous.

Today, we live in a more globalized world. For that reason, artists who want to become really eminent are obliged to travel continually to different countries in order to establish an international carrier. They should also participate in certain artistic residencies, several biennials or other big expositions and symposia.

Ptak, (2011), refers to residencies and says that “the basic goals of residency programmes is individual artistic development and the pursuit of experimentation. Nowadays, residencies are often incorporated into the core of artistic practice which allows geographical imbalances to be redressed, signalling an end to artistic discourses based on one-way traffic”.

As Denson (2012) also states “It's now over two decades since some of us--critics, theorists, artists--called for a nomadic valuation and criticism of art--a valuation and criticism encouraging us to diversify the cultural terrain with the contributions of indigenous artists the world over. If there is a nomadic enterprise today, it is no doubt that of the consumption of culture; and if there is a nomadic profession, it surely must be that of the globally-attuned artist.”

Additionally to this, from some years and on we are attesting a new phenomenon. Some artists choose to leave their rich home countries and move in emerging and developing countries for creative purposes. And after a long period of time they return home and present their work as being witnesses of another culture.

As Palomino, (2010) states “At the actual flow of globalized commodities, interchanges, transportation, technology, global financial investments, communicational networks, international migrations movements, tourism etc the figure of the artist has become a witness and an actor of his time.” This is the case of four following Greek artists we are going to present, Alexandros Georgiou, Georges Drivas, Nikos Charalambides and Dimitris Alithinos.. There are, certainly, some other important artists...

Alexandros Georgiou, 42 years old, was well known as a young artist in Greece, even from the time he was still a student in the Greek Athens School of Fine Arts, from the series of photos (of an intimate existential character) appearing in the “Spring Collection” exhibition of the “Deste Foundation” of the famous collector Dakis Ioannou. After graduating the School of Fine Arts he went to New York, he prepared a MSc at the School of Visual Arts of New York and participated in various international exhibitions.

Why did I choose to present him among others? The reason is because he is different. His difference from other similar nomadic artists is that he is not photographing neither exotic images nor melodramas or atrocities addressed to the Western eyes and international market. He is not creating photos of misery that humiliate Eastern people. He just collects relics, memories and embers of a culture that leans sinking to the West and sensitizes us about the real meaning of life. Another difference is perhaps the most important: whatever he lives, he lives it locally, from within and from his own for years now.

Alexandros Georgiou, Persepolis, Mixed media processed photo, Courtesy of the artist and Eleni Koroneou gallery

Alexandros, seeking for reality beyond media lies and the prejudice regarding life and art of the East, escaped from an atmosphere of the market and marketing of New York to a new, strong emancipation of his artistic representation by living and creating with entirely new materials from those of the West. In 2005 he decided to go to India and other Eastern countries and live there for a long time, till 2013. Returning he exhibited his artworks at the National Museum of Modern Art. Some questions emerge.

What really made Alexandros Georgiou to abandon his 7 year long stay in New York- the dream of every young artist of the “periphery”- and depart for his long term journey to India, Iran and Pakistan ?

Which was the path of his artistic quest up until then and what was his differentiation regarding the “reading of the world and art”?

Alexandros Georgiou, Without My Own Vehicle India – Kids Wearing MacDonalds Clown Masks 2006-07, digital print on paper

His images – fragments and the comments that he sent to a number of selected participants in Greece- are coloured by the immediacy of a painful everyday reality of poverty, by a hybrid mist that bonds the sacred with the commercial, by personal poetic images, by colourful visions of deities that are erased by advertisements but still remain alive in the soul as the last sign of hope and faith. These images of spirituality emerge as in communion with life and pain and are presented as pure, experiential, honest and immediate revealing their own aesthetic, that of solitary transience that leaves, however, a permanent mark of longing. They are the exact paradigm of what Agamben was describing with the term “bare life”. By this term Agamben, (1998), characterizes the made of life of many “excluded” and poor population, some kind of the “luben proletariat” in Marxist terms. . Alexandros is someone who familiarizes us with the “otherness” of the “bare life”. More in the following video…

![Nikos Charalambidis, Rietveld's Red Blue Chair blocked in a traditional loom [2006] Nikos Charalambidis, Rietveld's Red Blue Chair blocked in a traditional loom [2006]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEhwq4ivq96zR2PTgNrgC2UoN3Pk7DRtSmupWRzfHOk_8gyMBhxwKTZ6SBIwG9WpXYTTp3YrTeJcXBC_T7EVVypW1SbqO_eTQBxXORlZ5-g9cZii0EaDepU5CRk2f7cEEmvmWnUiP5lHKGNd/?imgmax=800) Nikos Charalambidis, Rietveld's Red Blue Chair blocked in a traditional loom, 2006 By Vassilika Sarilaki

Why did I choose to present him among others? The reason is because he is different. His difference from other similar nomadic artists is that he is not photographing neither exotic images nor melodramas or atrocities addressed to the Western eyes and international market. He is not creating photos of misery that humiliate Eastern people. He just collects relics, memories and embers of a culture that leans sinking to the West and sensitizes us about the real meaning of life. Another difference is perhaps the most important: whatever he lives, he lives it locally, from within and from his own for years now.

Alexandros, seeking for reality beyond media lies and the prejudice regarding life and art of the East, escaped from an atmosphere of the market and marketing of New York to a new, strong emancipation of his artistic representation by living and creating with entirely new materials from those of the West. In 2005 he decided to go to India and other Eastern countries and live there for a long time, till 2013. Returning he exhibited his artworks at the National Museum of Modern Art. Some questions emerge. His images – fragments and the comments that he sent to a number of selected participants in Greece- are coloured by the immediacy of a painful everyday reality of poverty, by a hybrid mist that bonds the sacred with the commercial, by personal poetic images, by colourful visions of deities that are erased by advertisements but still remain alive in the soul as the last sign of hope and faith. These images of spirituality emerge as in communion with life and pain and are presented as pure, experiential, honest and immediate revealing their own aesthetic, that of solitary transience that leaves, however, a permanent mark of longing. They are the exact paradigm of what Agamben was describing with the term “bare life”. By this term Agamben, (1998), characterizes the made of life of many “excluded” and poor population, some kind of the “luben proletariat” in Marxist terms. . Alexandros is someone who familiarizes us with the “otherness” of the “bare life”. More in the following video… |

READ MORE >>

4th Thessaloniki Biennale of Contemporary Art, 2013, Interview with Αdelina von Fürstenberg

V. S. Of course and this is very helpful.. In the catalogue you mention the economic crisis at the time of this biennale. You said: “In the last few years we are also facing heavy economic crises as well as identity crises all over the Mediterranean areas”...

A. F. In fact I work sixteen years for this organization called “ Art of the World”, which is a human rights organization that works with contemporary artists and through contemporary art reveals the positive and negative things happening to human values. Therefore in this context I really want the public who visit this biennale and come to contact with the artists’ world to develop a deeper awareness of the situation today; I wrote this text six months ago and today the situation is even worse – the economic crisis in Greece is even harder, the lack of freedom and the violence in Turkey and Syria, especially in the Eastern Mediterranean are worse. The Thessaloniki Biennale can speak openly about these things, first because it is in a European country with freedom of expression and because it is a country in crisis, but not alone in Europe. So the concept of the Mediterranean has enlarged now and has become more universal. Therefore people may understand that our aim is not to promote this or the other artists but to communicate messages. V. S. And you also mention in the catalogue that “We all know that the Mediterranean Sea is much more than a geographical expression. Referring to the amalgams of peoples, cultures and mentalities, it is a door open between East and West; a meeting point of three continents, Africa, Asia, and Europe.” That’s right. But can biennials — whether they're held in Venice, Thessaloniki or Jakarta — shape a greater sense of understanding and connection among different cultures and make the difference?

V. S. I want to ask you. . do you think it still makes sense to talk about national art today or not? Does it still make sense to talk about “being Greek or French” in a globalized world? Or, precisely because of globalization, should we be more local?

V. S. And very deep also… in time.. V. S. Yes. .and how do you see the Greek art scene today? A. F. How do I see the Greek art scene? Honestly I think that Greek artists, the Greek scene is very very, lets say, active. I think there are lot of activities in the Greek art scene – but I think they are somewhat divided between commercial and independent. V. S. What about the lack of international reputation of Greek artists? And why do you think that might be? A. F. That happens because the Greeks don’t know how to communicate effectively– they don’t consider promotion important. They have an old fashion way of communicating. The way of communication is still like in the eighties. I have to deal with this personally, myself now. . with the biennale, too. I mean the way the artists communicate has changed radically everywhere else in the world. But in Greece they still function in an old-fashion way, so these artists don’t appeal. A. F. How I chose the artists? V. S. If we exclude the visual “entertainment” of the biennale I personally believe that it surely required the presence of political themes in this exhibition. Many of the artworks you selected for the biennale are socially inspired. Is this because artists today are more engaged f. e Husein Karabey and Gulsun Karamustafa (Turkey), Nigol Bezjian (Syria), Claire Fontaine (France), Gal Weinstein (Israel) e. t. c, or was it your decision to emphasize political art in a large sense of course? A. F. Yes. .This is totally true but in a sense that I don’t think we should call it political art, we should call it contemporary art. . And we should call it independent art – art that wants to express things not just art that addresses itself to the rich collectors or funds. So this art makes you think, this art gives you information, this art makes you understand the context we live in. This doesn’t mean that I want to change the mind politically. How can you do a show in Greece today or anywhere in Europe and avoid the difficult issues and make cute art only for the elite? It’s impossible.. Art is for everybody, art is not for the few – It has nothing to do with the few – art is for few to buy but it is to be enjoyed by everybody. V. S. Do you believe that art can inspire personal or social change? A. F. That is something very difficult to say. Take the case, for example, of the Iranian filmmaker Jafar Panahi, who is also in my show, he is one of the most important film makers, we produced his film together; he was in jail when we produced it and he was condemned. This film was shown everywhere. But still this guy was condemned. This means that art can give inspiration, can make people think but I doubt whether it can really influence the politicians. Because artists are not politicians - therefore is important not to confuse the role of the artists. You understand what I mean.. V. S. Yes, of course I understand. . And how do you think the crisis is affecting artistic production? A. F. A lot. Crisis is affecting, as you say, artistic production. Crisis does not obstruct art or creativity. Crisis disrupts the production of art because there is less and less money to produce art; there are fewer museums, galleries showing art, independent art –therefore the worlds of art is becoming very small. But actually there are so many artists, so many people who want to express themselves through art. Good or bad – I’m not talking about quality now. We are thinking of art as expression. And the crisis affects it a lot. V. S. The art market is very strong today, and the world is full of art fairs and festivals. Do you believe that the Biennale of Thessaloniki could have some importance in this context? A. F. I don’t think so, because the choice of the artists is not part of this context. Because we don’t have the superstars. But it is also not what I do…I mean, I choose artists working for human rights. So how could one imagine that I will do a biennale that will have all these fancy artists? The artists I chose are very good artists who have exhibited to Documenta, in galleries everywhere in the world. But they are committed to an ideal. And not to the market. A. F. No, no we are in a very difficult situation, but everybody knows that. Our main problem is communication, because that t has to be done well. So I’m thankful to you that you are already doing something. Also the Organisation “Art of the World” is working very hard for me to help advance communication and everything.. Because I think this biennale of Thessaloniki could be extremely important because, in this context of today, first of all we have exhibitions all over the city and then we have these large spaces, the pavilions of 2.500 m3. A lot of things will be exhibited.. V. S. It’s a very large biennale that’s true.. The strategy V. S. Yes.. A. F. I mean “reading” every piece, thinking about it, enjoying being there and at the same time understanding that art can play a role in society. V. S. I wonder. . Has the audience changed in contemporary art since you have been working in it? Is the Mediterranean audience different from the Northern European? A. F. I think that the audience has changed dramatically the last 10-15 years because there are too many people interested in art now. In the past there were just a few people but they were sincerely involved with art. Today they are many many people in search of art but I don’t know if they are really interested in it or in its social (fashionable) context. In this biennale you can both enjoy what you see and provoked to think at the same time. And also the Greek artists that I have chosen are on the same wavelength as me. They are all artists who are concerned about social issues. Of course we will see if the end result is what I’m talking about but I hope it will work. V. S. Well, good luck to your exhibition and thank you.. A. F. Thank you so much.. |

Nikos Alexiou

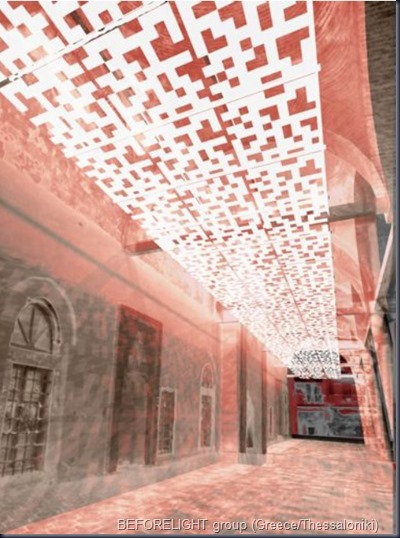

Wikipedia"The End"Regarding Nikos Alexiou participation in Venice Biennale 2007, Vassilika Sarilaki, a known Art Historian, interviewed him. Interview and text was published entitled In Trance in Highlights Magazine:  A master of space and the sense of the borderline, Nikos Alexiou, an artist known for his delicate works and motifs, his paper embroidered with perforations and his frugal constructions, will be representing Greece at this year’s Venice biennale. The title of this year’s biennale,(2007) which will be held between June 10 and mid November, is “Think with the senses -- feel with the mind. Art in the present tense”, and Nikos Alexiou’s sensuous installation seems to get to the very heart of the matter. Starting out with the wonderful motifs in the floor mosaics of the Oberon monastery, which he reproduces in endlessly varying colours and designs to articulate an ecstatic world of beauty and moderation. His is a ‘structured chaos’ which balances the geometric nature of the material with the spontaneity of gesture. Alexiou’s work emerges once more not as a product of a prefabricated idea, but as the source of an all-embracing gift to the beauty of forms. As a product and an engagement of his bodily devotion to it. And it is this which ultimately bestows a natural grace and an aura of redemption on the work.  Alexiou means tradition in the sense ascribed to it by Husserl. That “painting’s past creates a tradition in the artist, a duty to start over differently; not survival, which is the hypocritical form of forgetfulness, but effectual reclamation, which is a noble form of memory.” It is this “reclamation of memory” through the experience of familiarity that he attempts to convey today, though he allows the viewer to see the work unfettered and to lose themselves in the ecstasy of the small, psychedelic world it proposes; a world dotted with coloured motifs which flow in space, with tender sketches of the monastery and intricate digital labyrinths on video. Taken together, the recollective designs, the fragmentary motifs moving imperceptibly on video, constantly changing shape, and the intricate patterns suspended in mid air define a new aesthetic world open to the imagination, to experience, to the viewer’s “individual breath”, and in so doing render largely relative the classical view of stability and the objectivity of space. Meaning the guise of material crops up again and again as a concept in Alexiou’s work as a pretext for taking a fresh look at our inner world and the way it is naturally reflected on the outside. And this might ultimately be art’s prime subject.Interview

Nikos Alexiou: The work functions as a theatrical machine. Because the way it is set up ‘plays’ with the viewer. Inside its gate, there is a large screen with a video projected on it which invites the viewer to proceed further in, essentially to wander around on ‘stage’, into the heart of the machine. Meaning the viewer doesn’t watch from outside; he enters something that surrounds him on all sides. Behind the screen, there is a series of intricate hanging ‘embroideries’ which mirror the banners with different designs from the Iveron monastery.

These things are strange, as you know. You come into contact with something and you don’t know what it is that moves you… It could have been something else. But this floor was in the very centre of the church, and living in the monastery you would cross it several times a day. So the reasons I chose it were related to my experiences of it, and with my familiarity with it.READ MORE >> |

The Triumphs of Oedipus

By Vassilika Sarilaki *

The most powerful experience of art is when the work of an artist leaves one speechless. When one emerges from the mists of “ineffable speech”, as Valery defined it, no amount of verbal caresses can encompass it. Costas Tsoklis has reached such a celebratory moment, and he talks to us today, at the age of 76, about the most important work of his career. It is the “Oedipus in Conclusion”, a powerful, moving, human piece; masterful in the life messages it transmits; perfect painting and dramaturgy.

READ MORE >>

Talking About Athens

![vass_thumb[10] vass_thumb[10]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEhLxLJNDzjjM1TXjt8IE1elJThUIijNaFG7SOUDW1B_K4ISAds2OfABD3dhoGdMbozCCLNxKmLgM1kRbtdS6v5GOJjPaSyJPYg8vdTKLYiQHecVuA1GV1-qk69Y9GxHySzK8jLEwof7Cnuj/?imgmax=800) The following is a discussion/intervention concerning the burning problems of Athens, its aesthetics, the relation between sculpture and architecture in the city and the new models of contemplating it. The participants are: Denys Zacharopoulos, Professor of Art History at Amsterdam’s Arts Academy and the University of the Aegean, former Inspector General of Modern Art of the French Ministry of Culture, and co-director of Documenta 9, in 1992; Yiorgos Tzirtzilakis, architect and art critic; and the sculptor Thodoros Papadimitriou, former Professor of Plastics at the National Technical University. Coordinating the discussion is art critic Vassilika Sarilaki.  Vassilika Sarilaki. Athens is an anarchic city of constant contradictions and surprises. It originated from the exclusion of the refugee settlements; it experienced the ‘glory’ of exchanging houses for apartment blocks during the dictatorship; its citizens build unlicensed homes; its ministers build unlicensed villas; its municipalities build without a license on its beaches. And then the State comes along and legalizes them. At the same time, there are downgraded zones and new immigrant ghettos in the center, while we also see the results of the new vested interests of modernization, such as the construction by Vovos, and the nouveau riche entrenchments of the northern suburbs. Moreover, the city is one vast construction site in view of the Olympic Games, which adds to our sufferings. What is in force today is a regime of "multiple singularity", as the architect Takis Koumbis so graciously put it; an egocentric philosophy of "not bothering", where both the citizens and the State act as private individuals, with no regard for any unity in urban planning. Given this environment and under these conditions, what can today’s urban planner or architect propose? And would there be a point to such an intervention? For there are schools of thought which oppose the taming of these contrasts, deeming disorder and improvisation to be components of the living personality of Athens. READ MORE >> Costas VarotsosMaria Papadimitriou, In the courtyard of memoryREAD MORE >>

NICOS CHARALAMBIDIS, Interviewed by Vassilika Sarilaki

NOCHELEIA: the C.I.A. Project, 2006, Turner Contemporary Art, London

The career of Nicos Charalambidis, the multitalented and subversive artist, has shot into orbit in recent years. London’s Turner Contemporary Art will be showing a new, powerful, politically charged exhibition of his work throughout the summer as part of a multi-faceted project including reconstructions of emotionally-charged monuments, the Nicosia wall, video, workshops and a hosting platform with invited artists, including Walid Raad, Artur Zimijewski, Diego Perrone and the Atlas Group. Moreover, autumn brings with it the São Paolo biennale… _You are preparing an important exhibition at Turner Contemporary Art in London . In this new political/interactive installation, you make a core reference to the Nicosia wall, to the Situationists, the anti-architecture of the Sixties, and more. How do all of these relate to the overall concept, and how do you use the Turner’s space? Let’s start with the title, “NOCHELEIA: The C.I.A. Project”, which gives the viewer the impression that what they are about to see relates to some CIA secret mission with a Greek codename: “nocheleia” [languor]. It’s obviously an oxymoron I chose deliberately as the Social Gym, the activist programme of actions I follow, challenges social inertia and passivity of exactly this sort. The C.I.A. Project (Cultural Imperialistic Activities), on the other hand, references the troubled situation in Cyprus and the Middle East . It is significant that the artists hosted by the project are the Atlas Group. _In Green Line, your artistic intervention from 1989, you reference the Situationists. Now you are returning to them. What direction is this going to take? The exhibition focuses on the Situationists, and especially on Cedric Price, the famous London architect who spent a lot of time working on funfairs and places of entertainment. The area around the Turner has long been dominated by this sort of carefree atmosphere, and it is home to Europe ’s most famous funfairs--which have now been declared protected monuments. Architecture students from Canterbury University will link their projects to the subject-matter of this exhibition. The workshops are one of the parallel activities, as is the performance with the Gurkhas, the British brigade currently escorting the Prince of Wales in Iraq . _Will the exhibition follow your usual practice and feature a range of constructions and videos? Video projections are a central part of the exhibition, as is the reconstruction of the monument to Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht the Communist Party commissioned from Ludwig Mies van der Rohe in 1926, and which the Nazis destroyed shortly afterwards. Mies emigrated to new York , and it wasn’t long before he was being described as one of America ’s leading architects. But that monument continued to be a black mark against his name. They say the CIA tried to spirit the blueprints for the monument away, and Mies was forced to carefully suppress all mention of this project. _Yes. There are some dark areas. Jean-Louis Cohen recently wrote that Mies made the monument, but flirted with the Nazis at the same time. If we also bear in mind that he took over as director of the Bauhaus in 1930, immediately after H. Mayer (the former director) fled to the Soviet Union after the Nazis subjected him to particularly savage attacks, we can conclude that Mies was accepted by them to some extent… The exhibition highlights exactly these contradictions. The monument to Communism is contrasted directly with the subject-matter and title of the exhibition, which alludes to the CIA. On the other hand, the installation’s interior space, which is like a cave, is useful as a refuge, as a dark video booth for the forbidden (in Europe) films of an artist from the Atlas Group, Souheil Bachar, who was held hostage in Lebanon for 10 years. _So it’s a purely political exhibition, if you consider that it refers to a period of political ferment: from 1919 (Luxemburg’s murder, establishment of the 3rd International and Mussolini’s fascist party, revolutions in Central Europe) to 1926, the year of the Mies monument. Coincidentally, Fritz Lang made Metropolis, the inspiration for the use of the replica in your works, in the year the monument was built. Meaning that in your house in 1990 you made the first replica of Mies’ Barcelona Pavilion, which you later used in various installations, at the Venice biennale etc. Why the insistence on symbolically reconstructing historically charged monuments? It’s interesting to take a look at the history of the pavilions and the constructions designed from the 19th century on for one international exhibition or another. Many were never actually built (Tatlin’s monument, for example), and the great majority were destroyed when the event ended (like the Barcelona pavilion). The Eiffel Tower is one of only very few that fate smiled on. I am particularly moved by an era’s destroyed constructions/symbols. Nicosia airport, Berlin ’s Kant Garage, the Philips Pavilion, Kurt Schwitters’ Merzbau, Konstantinidis’ wrecked Xenia hotels... The war on Cyprus in the Seventies was fought against a backdrop of Modernist buildings. One of my most intense childhood memories is of Nicosia airport. My first experience of aeroplanes, the first escalators, which my child’s eyes imagined as slides in a playground, the round Pop armchairs that looked like amphorae, the glass room from which you could look down on the departure lounge and keep your loved ones in sight until the very last minute… all of this transformed the building into a magic Disney Land building. Years later, I began to realize that in addition to my experiences of Cyprus ’ brutally levelled Modernism, many of the most typical examples of this period had been left to their fate, abandoned and deserted. When I visited Le Corbusier’s Unite in Marseilles in 1990, I was struck by the terrible state it was in; it looked like a refugee complex. The references to this period take on an allegorical character in my work, highlighting the politics of modernism, the strategies of the Cold War. _Meaning that another factor that seems to have intrigued and aroused your interest in working with the Rohe monument, is the architect’s declaration that he made it out of everyday bricks, reproducing a wall against which they had executed dozens of Berlin Communists… The wall concept you employ so often and the idea of violent separation dominate your work. The division of Ireland and of Palestine , the underground shelters, the Taliban prisons, are your subjects par excellence. So today, now that political art is back in fashion, what do you have to say about the numerous artists and curators who are resorting to a belated interest in Cyprus ’ Green Line? It is, unfortunately, true that after Cyprus was officially selected to host the Manifesta, curators and artists—most of them Greek, unfortunately—discovered the Greek Line somewhat late, and displayed a delayed interest in the island’s political problems in a climate of unconcealed opportunism. Ultimately, you could probably say not even the three Manifesta curators managed to grasp the singular political situation on Cyprus . Indeed, one of them requested that his department take up residence in the occupied North in disregard of the official Cypriot government that had invited him, and asked the refugees taking part to pass through the road blocks every day, and thus have their passports stamped with the visa of the illegal government of Northern Cyprus . _Having kept a close eye on your work and aware of the requests you have submitted from time to time to the Cypriot Ministry of Culture to stage cultural events on the Green Line—none of which have come to anything, I was truly sorry and considered it unfair that you were not invited to take part in the Leaps of Faith exhibition. Especially since your exhibition at the Venice Biennale dealt, once again, with the Green Line… I was less annoyed by my not participating in the exhibition than by the provocative—and deliberate—silencing of my work at the parallel conference and the non-inclusion of my work in screenings of political works and interventions. The worst thing of all was the argument put forward by the curators, who said I couldn’t take part because I was a Greek artist. Of course, Hussein Chalayan, who has lived in London since he was a child and who has officially represented Turkey , was automatically considered a Cypriot… _What can I say? Let’s move on to something more pleasant. What will you be showing at the São Paolo Biennale? I will dismantle three specific barrel-barricades on the Nicosia Green Line and will transport the barrels to São Paolo, setting the tone of this year’s event, whose central title is “How to Live Together”. * Nikos Charalambidis’ exhibition at the Turner Contemporary Art in London will be on for three months, from July until September. The São Paolo Biennale, this year entitled “How to Live Together”, will be held in October until December, 2006. |

As far as I know, you’re too polite, you’re not cutting either ears or noses from anyone and in addition, I have to say that some ads aren’t exactly art works. Instead you give some harmless advice or make some comments. Is this Vandalism or social offering?

As far as I know, you’re too polite, you’re not cutting either ears or noses from anyone and in addition, I have to say that some ads aren’t exactly art works. Instead you give some harmless advice or make some comments. Is this Vandalism or social offering?![A Girl in Red Dress with Cat and Dog, Updated (Ammi Phillips [1830] & Jilly Ballistic [2013]; 5th Ave 53rd St; MoMA platform) A Girl in Red Dress with Cat and Dog, Updated (Ammi Phillips [1830] & Jilly Ballistic [2013]; 5th Ave 53rd St; MoMA platform)](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEi2BFoQY29N5zZzmil4RgUiOuLiNRwubqa4ZinrrgxtL6x4wTbnvrsCKQwicqiBNSHe6_H9WuXzjkt2LR_ZWqccuMXJWfxU3-OHSkFZeZBoqcni4SzT1er6UUt6VPU5-E_kghkJrRgyltn2/?imgmax=800)

![Where cravings meet [insulin shots.] (Greenpoint Ave; Church bound G) Where cravings meet [insulin shots.] (Greenpoint Ave; Church bound G)](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgAjs4MAkTtybbR-g6A2uLYntmvHrBiNsURAqu2Rvhw5cWxdub7l99YaRENHEKNd-fplZCWAP8V88KtcqLpr3W6cvS9P-HUht4GiHJ9GHvtQsMtxzqWC8WQdhye7sY_87eMln86_QluDt1O/?imgmax=800)

What will the installation you will be showing at the Venice biennale include exactly, and how will it be structured?

What will the installation you will be showing at the Venice biennale include exactly, and how will it be structured?