In the light of the exhibition of portraits by the well-known painter Panagiotis Tetsis that was held at the Nees Morfes gallery (2005) we met up with the artist to discuss his long career, the ups and downs of painting, and the younger generations of artists. By Vassilika Sarilaki *

Vassilika Sarilaki. -You’ve been painting for 55 years on the trot. You’ve been painting portraits in particular since you were 25 years old. What did you notice about the human form then and what now? What’s changed in portraiture? Panagiotis Tetsis . -I was painting portraits even before I went to the Athens School of Fine Arts. I’d painted my mother, my self, friends and others. Certain things may have developed over the years, but my main focus has remained the same. I never wanted simply to depict, to paint an almost photographic reproduction; I wanted to capture the person’s full-length form, the way they think and behave through their movements, their hands, the way they stand. I paint the whole person. I’ve only done a few heads. A person expresses their mental world through their body and especially through their hands. Of course, this is even more true of us Mediterraneans, whose bodies and, of course, hands—are constantly mobile. V. S. What was the most important thing you learnt from Pikionis and Ghikas, the two artists you consider your most significant teachers? P. T. Their views on art, which were more modern than those held by the remnants of the Munich School that still dominated the Athens School of Fine Arts at the time. I’m not condemning the Munich School—in fact I have a lot of respect for it because it produced a number of great artists, including Gysis, Lytras and Iakovidis—but Pikionis and Hadjikyriakos had taken on board twentieth-century conceptions of contemporary art.  V. S. Were you in contact with T. Tsingos and G. Gaitis between ’53 and ’56 when you lived in Paris? Were you influenced by their expressionist style or by other French artists? P. T. They didn’t influence me at all. We were all quite friendly. Tsingos was a really sweet person and his painting suited me more than Gaitis’. I was into a lot of contemporary French artists, but France had pinned all its hopes on Buffet back then. His painting was monumental, and he’d addressed certain topical themes of the era, including the harshness of war. Unfortunately, the wind went out of his sails after that. De Stael is the painter I consider most important. His work is graced with soul, sensitivity and daring. They appreciate him even more now that he’s dead.

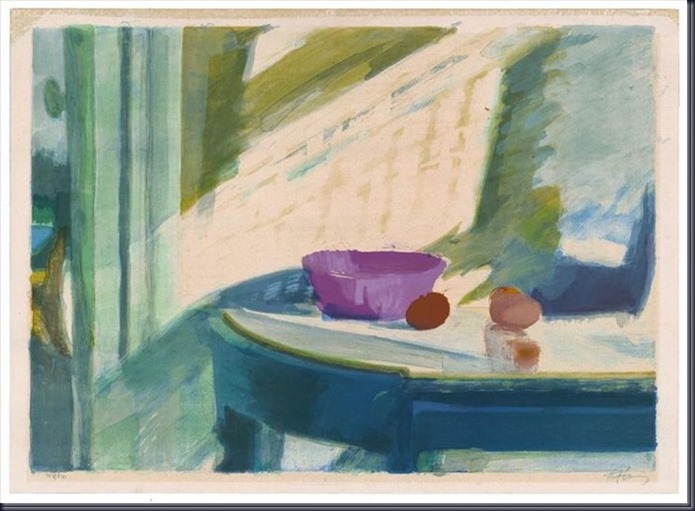

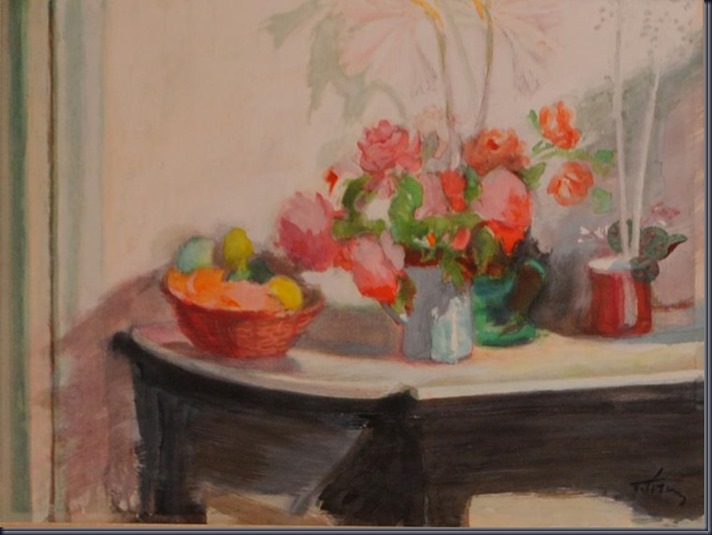

V. S. You’ve said you like the work of Michalis Economou. What a great painter! Light, colour, metaphysical depth… P. T. Of course, all that. Michalis Economou was a great artist, just as Nikolaos Lytras was a very important painter. V. S. You’ve been painting landscapes since the Sixties. Views of Sifnos and later very fine oils and watercolours of your home island, Hydra, neoclassical mansions and the like. Modernism was at its most frenzied at the time, and certain of your colleagues—Kessanlis and Takis among them—had declared themselves committed enemies of canvas. Weren’t you upset that they considered your work classical? P. T. Early on, after I came back to Greece in ’58, they considered my work very daring. Later, when the perception caught on that you had to be ‘abstract’ to be an evolved artist, I was considered something of a black sheep, but they slowly realized that my work had the merit of quality, that it was honest and free of extremes. And I think everyone came to appreciate that in time, even those who’d had nothing but scorn for me back then, saying “the poor man’s had it, look how backwards he is, stuck on painting”. They had it in for me because I was painting, and figurative works at that. But for me, representation is just my starting point, not my goal. If you look at my works carefully, you’ll see they’re hardly representational at all, that they just happen to be figurative; that deep down, the paintings are organized in a way that can lead to complete abstraction. They’re a bit condescending toward me. But what can you do?

V. S. It’s true that despite the numerous occasions on which painting was declared dead during the 20th century’s, the art-form has bounced back in a more conceptual form. P. T. Allow me to cite the example of a young friend of mine who staged a show in New York’s Hellenic Culture Centre. People employing objective criteria said he’d made a great impression. A lot of people went, in fact there were a lot of people who went every day, saying they rarely got the chance to see such good painting any more. And the New York Times art critic dedicated a whole half page to singing his praises. A half page? A couple of lines in that paper’s a big deal! V. S. You must mean Giorgos Rorris. He’s come on a lot in recent years. P. T. Let’s keep things general. There are a lot of good young artists in Greece.

V. S. Yes, but as you know from your time at the School of Fine Arts, from ’76 when you started teaching to ’92 when you left as Chancellor, fewer and fewer artists turn to painting. Would you say the younger generation’s painting quests have been enriched or detracted from by the new media? P. T. Every generation has its own roots and means of expression and reaps its own rewards. As for the new media, video, Internet and the rest, I’m not really all that familiar with them.

V. S. Which contemporary foreign artists do you hold in high regard? Lucian Freud, Richter… P. T. Lucian Freud is even older than I am. He’s a great artist. He’s kept on gradually moving ahead, and some of the works he’s painted in the last two decades are amazing. I think he deserves his reputation with the general public that has made him, from what I hear, the most expensive living painter in the world. Auerbach, who paints in the expressionist style, is also good. If you look closely, you’ll see that the most powerful artists tend not to be of British extraction, but imports. Lucian Freud, for example, is a German Jew, Sigmund Freud’s nephew. V. S. Some of our artists would enjoy a greater response if they lived abroad. If Nikos Houliaras, for example, was in Britain, couldn’t he be as famous as Hockney? P. T. Sure, Houliaras is exceptional. Both he and Semitekolo are very fine artists.   V. S. You’ve said Greece today doesn’t produce new ideas or new conceptions on culture. P. T. Yes, Greece has always been a country that follows. V. S. Why is that? What’s to blame? P. T. Lots of things. Our being on the edge of Europe while the action is in central Europe, in France and Germany and before that in Spain. And, of course, while the Renaissance was flowering in these countries, Greece was subject to an uncivilized conqueror. You can underline that. I don’t like the Turks. Because their legacy is a curse: we can’t raise our heads high. Just think how little time there was between great talents like Gyzis and Lytras and the War of Independence: not even half a century. It’s a miracle they emerged in such a short space of time.

V. S. What would you like to go down in the history of Greek painting for? Most experts consider you a superb colourist, others focus on your rendering of the Greek light. P. T. Why should they separate them. I don’t understand that. Art critics always want to put the two in separate compartments, but light, drawing and colour coexist, they’re together. V. S. As the years go by, has painting got easier or more difficult for you? P. T. It’s always difficult. And I say that sincerely. It’s always difficult. You need to sweat a lot. In the beginning you have an image of the composition. Then you choose the weights, the contrasts, and things often crop up that subvert the initial conception completely. But I still always enjoy painting.

V. S. Looking back, what would you recognize as your best-loved work? I don’t know. A boat I did that’s part of the donation I made to the National Gallery. A boat…alone…viewed from above. V. S. Why do you like the boat? P. T. Why? Because it exudes loneliness…and the water looks dark from above, and you can just make out its sheen from below…you’ll know what I mean if you see it. You can see it in the exhibition I’m staging at the Goulandris Foundation in the summer. V. S. I’ll make sure I do. Thank you very much.

*Vassilika Sarilaki is an art historian. |

Δεν υπάρχουν σχόλια:

Δημοσίευση σχολίου